Compilers are fundamental software tools that transform human-readable source code into machine code—a language that computers execute directly. This transformation allows developers to write complex programs in high-level languages while enabling efficient execution on diverse hardware platforms.

The Role of a Compiler

At its core, a compiler bridges the gap between high-level programming languages and low-level machine code. Unlike interpreters—which process code line by line—a compiler analyzes the entire source code, checking for errors, optimizing performance, and producing a complete executable. This rigorous process not only improves execution speed but also catches errors during compilation, reducing runtime bugs.

The Compilation Process

The compilation process is typically divided into two broad stages: analysis (the front end) and synthesis (the back end). Additional processes such as linking, loading, and sometimes just-in-time (JIT) compilation further extend this pipeline.

1. Analysis Phase (Front End)

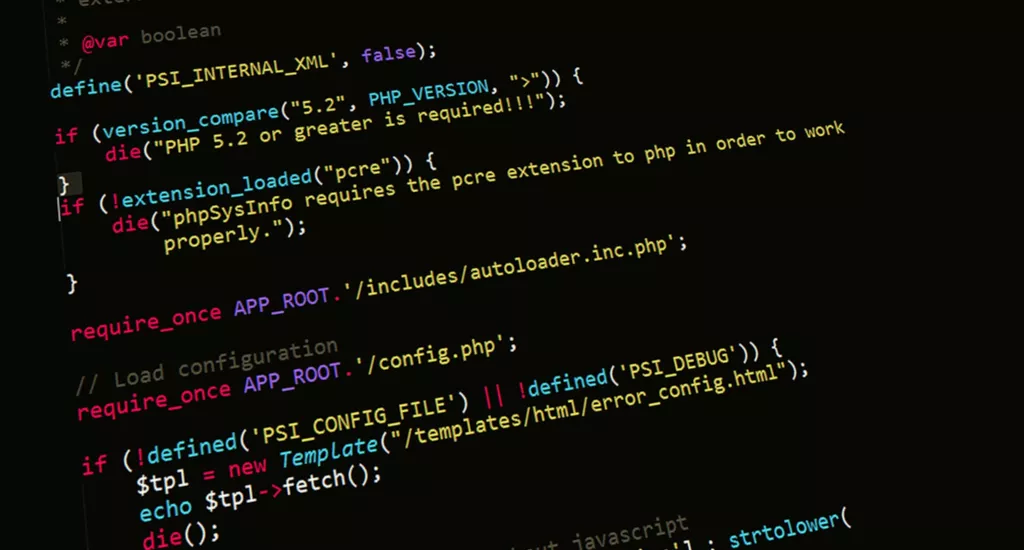

- Lexical Analysis:

In this initial phase, the compiler reads the source code character by character to form meaningful sequences called tokens (e.g., keywords, identifiers, literals, and operators). This tokenization converts raw text into a stream of tokens that simplifies subsequent processing. Advanced lexical analyzers can also handle language-specific features like macro expansion and preprocessor directives. - Syntax Analysis (Parsing):

Tokens are organized into a hierarchical structure, typically an abstract syntax tree (AST), based on the grammar of the language. This phase verifies that the code conforms to the syntactic rules of the language. Modern parsers use techniques such as recursive descent, LR parsing, or LALR parsing to construct the AST efficiently. - Semantic Analysis:

Once the AST is built, the compiler examines it for semantic correctness. This includes type checking, scope resolution, and verifying that operations are applied to compatible types. It also involves building symbol tables—data structures that track identifiers (variables, functions, etc.) and their attributes (type, scope, memory location). Semantic analysis can also perform preliminary optimizations by simplifying constant expressions.

2. Synthesis Phase (Back End)

- Intermediate Code Generation:

After ensuring semantic correctness, the compiler translates the AST into an intermediate representation (IR), such as three-address code or Static Single Assignment (SSA) form. The IR is usually machine-independent, enabling further optimizations without worrying about target-specific details. - Code Optimization:

The IR undergoes various optimization passes aimed at enhancing performance and reducing resource usage. Common optimizations include:- Constant Folding: Evaluating constant expressions at compile time.

- Dead Code Elimination: Removing code that never executes or whose results are unused.

- Loop Optimization: Techniques such as loop unrolling, invariant code motion, and loop fusion to improve efficiency in iterative constructs.

- Peephole Optimization: Examining and replacing short sequences of instructions with more efficient ones.

Advanced compilers might also perform interprocedural optimization (across function boundaries) and register allocation using algorithms like the Sethi–Ullman numbering.

- Code Generation:

The optimized IR is then translated into target-specific machine code or assembly language. This phase involves selecting appropriate machine instructions, allocating registers, and scheduling instructions to minimize execution delays. Back-end optimizations are tailored to the target CPU’s architecture, taking advantage of features like pipelining and parallel execution units.

Additional Processes

- Linking and Loading:

After code generation, the linker combines multiple object files (and libraries) into a single executable. The loader then assigns memory addresses and loads the executable into memory for runtime execution. - Just-In-Time (JIT) Compilation:

Some modern languages (e.g., Java, C#, JavaScript) use a hybrid approach that combines compilation and interpretation. A JIT compiler converts bytecode to machine code at runtime based on profiling information, thereby optimizing frequently executed code paths. - Ahead-Of-Time (AOT) Compilation:

Alternatively, AOT compilers convert high-level code into machine code before execution. This method can reduce startup time and improve performance in environments where runtime compilation overhead is undesirable.

Compilers vs. Interpreters

While compilers translate the entire program before execution, interpreters process code line by line at runtime. Interpreted code can offer faster development cycles with immediate feedback, yet compiled code generally achieves superior runtime performance. In some modern systems, a blend of both approaches is used to balance development speed with execution efficiency.

Advanced Topics in Compiler Construction

- Front/Middle/Back-End Architecture:

Modern compilers often adopt a modular architecture where the front end (lexing, parsing, semantic analysis) is separated from the middle end (machine-independent optimizations) and the back end (target-specific code generation). This modularity allows the same front end to be reused for different target architectures. - Error Handling and Reporting:

Effective error detection and reporting during the early phases of compilation help developers quickly locate and fix issues. Compilers often provide detailed error messages, including the source code location and potential fixes. - Compiler Correctness and Verification:

Ensuring that a compiler produces correct code is a challenging aspect of compiler design. Researchers use formal methods and rigorous testing to validate that each phase of the compiler adheres to the language specification, minimizing subtle bugs that can be hard to trace in the generated code.

Sources: GeeksforGeeks, Baeldung, Guru99, TutorialsPoint